Are the Synoptic Gospels a Good Thing and What about Collusion & Contradictions?

In this blog I wish to briefly address the Synoptic Problem (or the Synoptic “Question” as I like to refer to it). However, before providing the most probable solution, I will first discuss some issues regarding the Synoptic Gospels.

- Why having 3 Synoptic Gospels is a very good thing.

Most students researching the Synoptic Gospels find some issues surrounding them quite perplexing. I would like to only add that this subject is a never-ending debate in which some people will never be satisfied. For example, if all three Gospels were virtually identical then some would scream “collusion,” and they would be probably right. Moreover, why would there even need to be 3 Synoptic Gospels if they were in fact virtually the same. In reality this charge could still be made with respect to their content because they actually do share so much common material. However, there are some important differences, differences that provide additional information about Jesus and the events that surrounded him, or that emphasize specific aspects of Jesus’ teachings more than the other 2 Gospels. So is this a good thing? Well, as I said, some people are never satisfied; consequently, any difference between them is an opportunity for others to charge that they contain inaccuracies, errors, and even contradictions. Regrettably, in our modern and post-modern world some demand unreasonable precision and almost “scientific” accuracy when dealing with historical events documented in the Bible. However, we are not dealing with modern reporters and audiences; instead we are relying up ancient authors whose audiences had no such expectations with respect to precision of historical events. Did they expect accuracy? Of course they did, but not the type of precision we today often expect when explaining history or reporting the news (a phenomena commonly referred to as the “CSI Effect”). Regrettably, some hold the Gospel writers to a far greater standard than other ancient historians such as Josephus or Tacitus. These scholars (e.g., those of the Jesus Seminar) approach the Gospels with a bias that suggests that if there is any doubt in any area, then there must be doubt about everything recorded in the Gospels. However, ancient audiences were not driven by such modern academic idiosyncrasies. Consequently, possessing 4 Gospels (including the Gospel of John) was viewed as a good thing for most within the first-century church. This is not to say that ancient audiences were not at times confused by some apparent differences in the Gospels, but by and large they (i.e., the church) appreciated having three Synoptic Gospels instead of just one, and so should we. Especially in the predominantly Jewish culture where the testimony of two to three persons was necessary to confirm the truthfulness of someone who claimed to be an eyewitness (Dt 19.5; Matt 18.16).

- Did Matthew write the first “Gospel,” and was that work “Q,” or was Q a different literary work that is now lost?

The testimony of history tells us that Matthew wrote the first “Gospel” and that it was written in Aramaic (see the testimony of Papias, ca AD 110). The majority of scholars who argue for “Q” assert that it was a Greek rather than an Aramaic document or Gospel (there is a small minority who suggest it was originally an Aramaic document). What makes this entire discussion concerning Q so frustrating is that today’s scholars seem to think that they can make up their own personal definition for Q and what it contained, and that is sufficient. To borrow an old joke, “If you put 10 different scholars in a room and asked them about Q, you will get a dozen different conclusions.” Personally, I do not believe that “Q” ever existed, and if it does exist then it is what we refer to as the Gospel of Mark. I am also of the opinion that all “L” material is originally from Luke rather than another “L” document, and that all “M” material is also originally from Matthew’s memory rather than another document used by Matthew. Consequently, my research indicates that Matthew first wrote an Aramaic Gospel for Aramaic speaking Jews in Judea (approximate date unknown), while Mark soon afterwards wrote the first Greek Gospel based upon Peter’s eyewitness testimonies and sermons while Mark was in Rome sometime in the mid to late 50s. Whether these 2 early Gospels looked similar is anybody’s guess.

Mark wrote his Gospel in order to explain the message of Jesus Christ (Mark 1.1) to the Greek speaking churches in Rome after Peter had left the city. History indicates that the believers in Rome requested that Mark write his Gospel since he was Peter’s disciple and partner in ministry. The church in Rome desired an accurate record of Peter’s memories about Jesus in order to understand all that Jesus had taught and accomplished on their behalf. Since this document was predominately the testimony of Peter it was perceived by the first-century church as the apostolic witness to the Greek-speaking world (to both Jew and Gentile) on the importance and significance of Jesus’ life and teachings. Remember, Peter was an eyewitness of Jesus’ life, one of his disciples, as well as one of his handpicked leaders for the church. In short, Mark basically wrote only what personally learned from Peter, and what he heard Peter preach and teach concerning ministry and life of the Lord Jesus Christ. Furthermore, while Mark was the author and Peter was his eyewitness source, the Holy Spirit was the guiding inspiration as Mark composed his Gospel.

A couple of years later Matthew depended and employed much of Mark’s Gospel in his second attempt at a biography of Jesus; however, this second Gospel was for Greek speaking Jews outside of Jerusalem or Palestine. Matthew, recognizing and knowing that Mark’s Gospel was predominantly the testimony of the apostle Peter, would have had absolutely no qualms with using Mark’s Gospel as a template while he wrote his new Greek Gospel for his Greek speaking audience (an audience that was also predominantly Jewish and part of the Diaspora). Remember, this type of plagiarism was acceptable in Matthew’s day. In fact, Matthew would have been expected to employ Mark’s Gospel while writing about the life and teachings of Jesus. It would have been unthinkable for him to have ignored such a significant and foundational document given his subject matter (i.e., the gospel of Jesus Christ). However, the Spirit inspired Matthew to include content drawn from his own memories, much of which was of Jesus’ personal instructions to his disciples, as well as his itinerant messages to the masses.

You should know ancient historians often embedded other important preceding historical works into their own histories, and this was normal fare when composing ancient historical works—and they often did so without any direct notation that they were depending upon the work of other authors. This is clearly observable to scholars that have researched Eusebius’s history of the church and other ancient pagan histories as well. However, as Matthew used Mark’s Gospel he improved upon its grammar and syntax, as well as added much of his own original eyewitness memories, some of which would have also been contained in his first Aramaic Gospel. That is not to say that Mark’s Gospel contained grammatical errors, but only that his writing style was not as elegant as Matthew wished. Consequently, these improvements in grammar and clarity found in the other Synoptics provides observable support for the position commonly referred to as Markan Priority (i.e., that the Gospel of Mark was composed before the other 2 Synoptic Gospels). Such observable improvements support Markan Priority since it is hard to believe that if Mark had used either Matthew’s or Luke’s Gospels to write his own that he would have purposely employed a less refined writing style while having a better style before him.

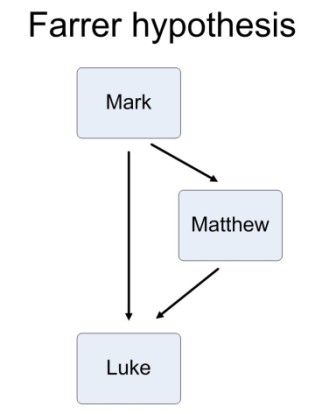

Luke, likewise, chose Mark’s Gospel as his foundational source, but he also included some material from Matthew’s Gospel, as well as material from his own investigation and interviews of Jesus’ disciples and apostles. Personally, I have very little use for Streeter’s theory concerning his “M” and “L” literary sources (these designations generally refer to other “written” sources not originating from Matthew or Luke). And with respect to Q, the truth is that any observable evidence (and by this I do mean all evidence) that can be used to support the theory of Q, can also more reasonably be used to support the assertion that either Luke depended on Matthew as one of his sources for his Gospel, or that Matthew depended upon Luke as a source as he wrote his Gospel. Personally, however, I am of the opinion that Luke had access to Matthew’s canonical Greek Gospel and used it as one of his main trustworthy sources for his own Gospel. Luke clearly stated in his prologue (Luke 1.1-4) that other historical narratives existed before he wrote his Gospel. Consequently, knowing that Matthew was a personal disciple of Jesus means that Luke would have no qualms with viewing Matthew’s Gospel as an additional reliable source as he composed his Gospel.

- Is it possible that Mark could have used another Gospel, whether written in Greek or Aramaic?

There is another consideration that many people (even some scholars) often overlook or ignore, which is that the Septuagint is a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible. While translating their Hebrew scriptures into Greek, it was important to Jewish scribes to make sure that they accurately translated the thoughts and concepts contained in their sacred writings into the Greek language (rather than making up new thoughts or teachings). Sometimes this could be done with a direct word for word translation, but often it required a degree of paraphrasing in order to provide an accurate translation of the thoughts and teachings contained in their Hebrew Bible. Consequently, using the Septuagint as a precedent, there is no rational reason that demands that parts of Matthew’s Aramaic Gospel cannot be contained in portions of Mark’s Greek Gospel – even though some scholars argue that Mark’s Gospel was produced from a “pre-Markan” document that was originally written in Greek.

Additionally, it should be recognized that it is possible that there were other earlier historical records that were “sources” for Mark’s Gospel (e.g., transcripts from Jesus’ trial before Caiaphas and/or Pilate), but these should not be labeled as “Gospels” since they were only “records” and not historical narratives. Consequently, with respect to the existence of a Q Gospel, this is theoretical speculation that I seriously doubt. History plainly indicates that Mark’s Gospel was based solely upon the personal testimonials of the apostle Peter rather than an Aramaic Gospel written from the hand of Matthew or an earlier unpreserved Greek Gospel. History is equally clear that Matthew wrote the first Gospel, and that he wrote it in Aramaic. Consequently, my opinion is that Q is an undocumented conjecture that should be given little credibility until corroborated by some physical or historical evidence. With this in mind, below is a possible chronology for canonical Gospels that were composted from the hands of the apostles or their close associates.

First: Matthew wrote the first Gospel and it was written in Aramaic, ca. late AD 40s to early AD 50s. To date no copy of this work has survived.

Second: Next Mark wrote the first Gospel written in Greek and it was based solely upon the memories of the apostle Peter; it was composed ca. mid AD 50s. It is my opinion that any Gospel now referred to as Q never existed. Consequently, Mark’s Gospel was the first Gospel written in Greek.

Third: Matthew, having moved to another location with a large Greek speaking Jewish population, later wrote his second Gospel, which was also written in Greek. Matthew relied upon Mark’s Gospel as well as his own memories as he wrote, and he composed this second Gospel ca. mid to late AD 50s. Being of the tribe of Levi (i.e., a priest), Matthew would have been trained in fashion similar to that of Paul; thus he would have known how to read and write in both Aramaic and Greek so that he could study both translations of the Old Testament scriptures that existed in his day (i.e., the LXX and the Tanakh). Moreover, being a tax collector from a primarily Aramaic speaking region he would have also been able to keep records in Greek for the Empire; consequently, Matthew would have been very competent in speaking and writing in both languages.

Fourth: Luke afterwards wrote the last Synoptic Gospel. He primarily used Mark’s Gospel, but he also used some material from Matthew’s Greek Gospel, along with his material accumulated from his own interrogation of close followers of Jesus, most of who were apostles. Luke wrote his Gospel ca. late AD 50s or early 60s. Very soon afterwards he wrote Acts, which was completed while Paul was still under house arrest in Rome, or very shortly after his release.

Last: While not a Synoptic Gospel, John wrote his Gospel; probably ca. AD 80s. John employed very little material from the Synoptic Gospels, although he did use some (e.g., the feeding of the 5000 and Jesus walking on the water).

In short, the historical and literary context in which the Synoptic Gospels were composed was one where shared material was the expected norm rather than the exception (compare 1 & 2 Kings to 1 & 2 Chronicles, as well as 2 Peter with Jude). Consequently, we should not be surprised that the answer to the “Synoptic Question” (rather than the “Synoptic Problem”) requires literary configurations that involve more than our modern minds are willing to consider. Nonetheless, the church and history are far better off for having 3 Synoptic Gospels rather than just one. And while this blog provides only one possible solution for the Synoptic Question, its assertions and conclusions are based upon observations drawn from a comparison of the Greek texts (i.e., a Greek Synopsis), as well as the earliest historical records concern the authorship and dates of composition of the Gospels found in the New Testament.

Doc.

Monte Shanks Copyright © 2010